Do Not Forget: A Painful Family Connection to the Past, A Lesson for the Future

Every family has significant stories to tell. Here is one of my family’s.

My maternal grandfather, Anthony “Bill” Casella, was one of the first Allied soldiers to see Dachau concentration camp in the spring of 1945, during the waning days of the Second World War. When the Americans arrived, they encountered thousands of dead prisoners, including 30 railroad cars filled with bodies in advanced states of decomposition. Most of the people still alive inside the camp were little more than ragged skeletons.

Nothing had prepared the U.S. servicemen for what they found at Dachau. The existence of Nazi forced labor and death camps had long been suspected, but the sheer scale of them–and the level of cruelty that had been inflicted upon the prisoners–shocked the liberating forces.

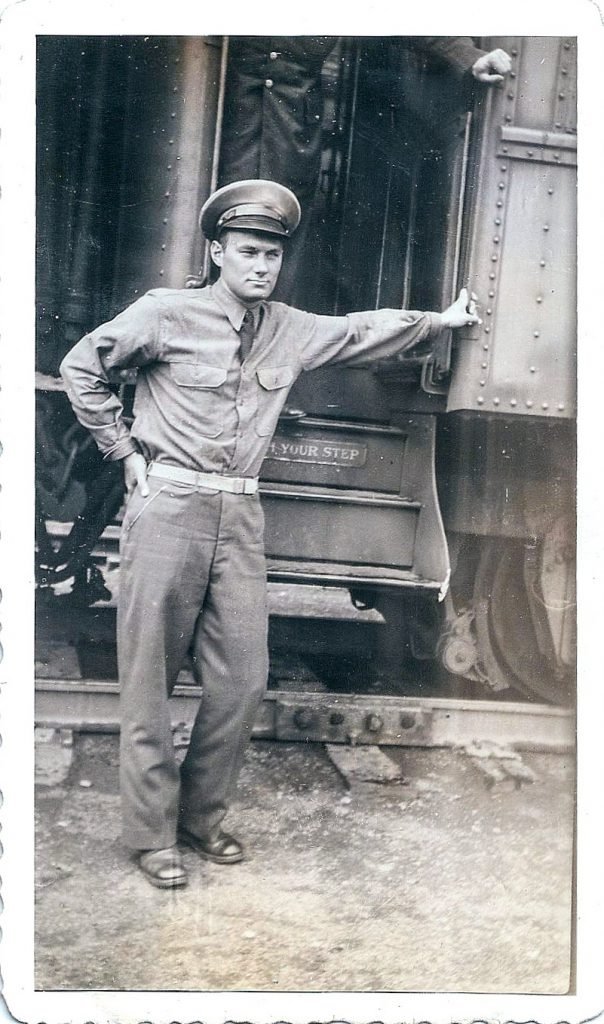

My grandfather, an Army medic who was 27 years old at the time, was tasked with aiding in the removal of corpses from the train cars, as well as helping sick prisoners receive medical care. It is a time in his life he never spoke of, as was the case for many U.S. service members who survived the war. Mental health care as we know it today didn’t exist back then. The term “post-traumatic stress disorder” would not be coined until 1980. The young men and women who served in the Second World War returned home, got married, had children, and tried their best to forget what they had witnessed.

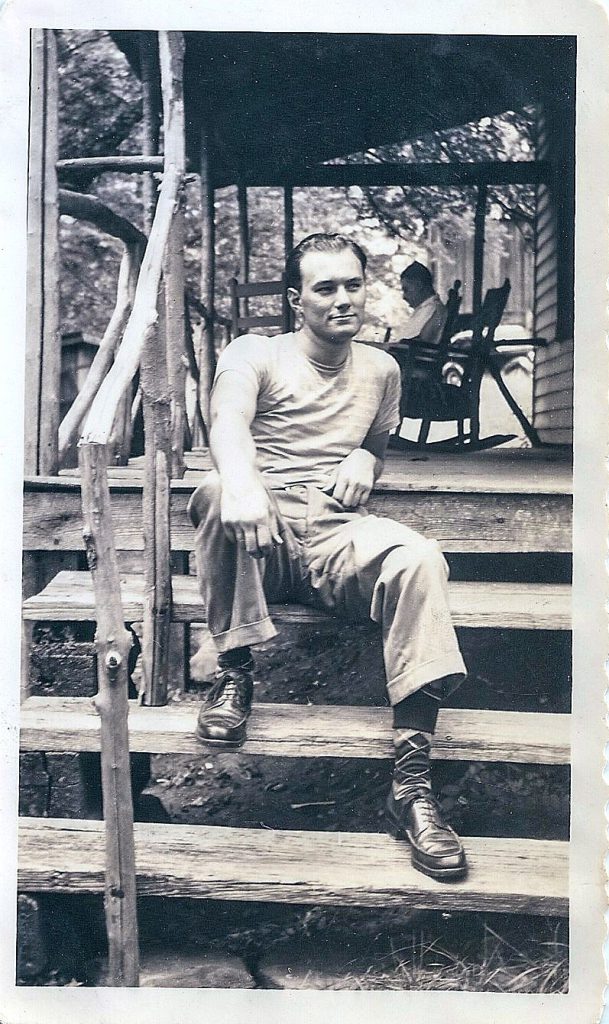

My grandfather was reserved but warm. He was a gifted carpenter and painter who could build anything from scratch. An old school gentleman, he always stood up when a woman entered the room. He was a skilled cook who made delicious meatballs and potato pancakes. A child of the Great Depression, he never wasted food, and I have memories of him eating the last bites off my plate when I was too full to finish. His car was his pride and joy; it was kept in such an immaculate state that not a single smudge or crumb desecrated its sanctified space. He read the newspaper from cover to cover every morning and enjoyed laying in the sun on hot afternoons. He died when I was 18 years old, the summer before I left for college. My sister, cousins, and I had the joy of knowing him for many years before liver cancer came for him at age 85.

I asked him about Dachau once about two months before he passed away. What was it like? I inquired, curious about his past.

Tears immediately pricked the corners of his eyes. “What they did to those people…” his voice trailed off softly, and he didn’t say anything more. I didn’t press him to continue.

After my grandfather died, I told myself that someday I would go to Dachau to walk the path that he walked, to try to understand what he had seen. Some might question why I would want to visit such a depressing place. I can only say that it has always felt essential to me.

The young men and women of my grandparents’ generation didn’t have a choice in how their youths unfolded. Forces beyond them determined they would be sent far away to fight among the palms and sands of the South Pacific or the ruined villages of Europe. Those same forces permeated my mother and father’s youths when the U.S. entangled itself in the jungles of Vietnam. Going to Dachau felt like a small way to acknowledge the pain previous generations had thrust upon them; a means of quiet tribute.

Mike, my mom, and I arrived at the Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site on a cool, rainy July morning. As we walked through the site, listening as the audio tour described the sinister purpose of each section of the camp, we were silent. The acts you hear about in detail, even if you knew about them beforehand, are horrifying.

Here is the place where new prisoners were registered, stripped of their belongings and identities. Here is the place where prisoners slept, jammed into tiny, dirty spaces meant for five times fewer people. Here is the place where prisoners were forced to stand every morning and evening, regardless of weather, regardless of illness or injury, for a pointless roll call ceremony. Here is the place where prisoners were executed. Here is the place where prisoners were burned. Every inch of the camp felt haunted.

I didn’t cry until we were sitting in the memorial site’s theater watching footage taken immediately after the liberation. People stagger around like living corpses, skin stretched over sallow, sunken faces. Railroad cars spill over with emaciated bodies, many with eyes and mouths frozen open in agonizing positions of rigor mortis.

I cried then, for the victims of the Holocaust, for all the people the Nazis deemed unworthy of life. I cried for my grandfather and his fellow soldiers, knowing they had witnessed these horrors. It seemed unbearably tragic that many of them locked away those excruciating images inside their minds for the rest of their lives, that cultural norms dictated their burdens couldn’t be shared.

I only took one photo at Dachau, of a sculpture inscribed with the words “Do Not Forget” in German, Hebrew, and English. This brief entreaty seems more important than ever in today’s world of rising nationalism and extremism. May we not forget what has happened before when one group of people were unjustly blamed for a country’s problems. May we not forget the sacrifices previous generations made so we could live in a free nation instead of one terrorized by an autocrat.

And may we not forget the dark chapters woven into the tapestries of our family histories, which, for better or for worse, have made us who we are.